I was a latecomer to Penelope Lively’s fiction for adults. Previously I only knew her name from her children’s books: The Giraffe, the Pelly and Me, to name one, or The House in Norham Gardens (since living in Oxford, I’ve had fun walking around the actual street named Norham Gardens, musing over whether Lively had any particular house in mind.)

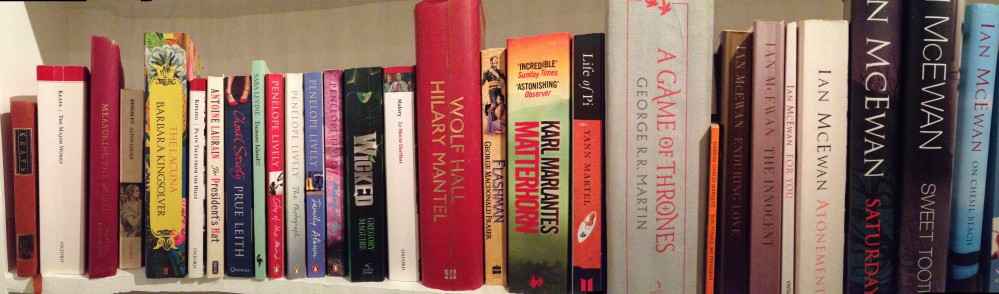

Consequences, read on a long, cramped train journey on a dark February night, was my first forary into Lively’s adult novels. Since then I’ve been voraciously working my way through her entire back catalogue. It’s great when an author’s writing inspires that kind of thirst, where one book makes you want to read everything else they’ve ever written. I’ve had it with Ian McEwan and Salley Vickers too, but I’ll praise them elsewhere; this is Lively’s party.

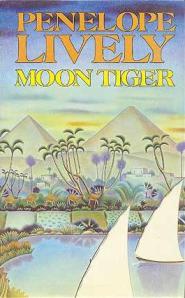

She deserves a party: she is undervalued. Why is the publication of a new Lively book (and she is a prolific writer) not trumpeted in the way that books by other major British novelists are? Mustn’t whine (Penelope would hate that) but there seems to be an impression, identified by Anthony Thwaite in his introduction to her Booker prize-winning Moon Tiger, that Lively’s books are essentially cosily middle-class, unchallenging reads. Nothing wrong with that, but that’s not Lively.

It’s true that her novels are peopled with middle-class characters pursuing white-collar or arty, imaginative careers. Academics (often historians or archaeologists), garden designers, architects, interior designers, writers, solicitors, journalists and art dealers all feature. But Lively likes skewering these types, too: Gina in Family Album is aware that her aunt Corinna ignores her mother Alison, a housewife, and is impressed only ‘by achievements in her own rarefied sphere. I don’t write studies of 19th Century poetry, so I am beyond her remit.’ Kath in The Photograph remains an enigma, a kind of aporetic void at the heart of the text, but this is because we only ever view her through the eyes of others who are constantly trying to grasp what she ‘does’ with her life. They don’t understand what she does for a job, if she does anything at all. Therefore they don’t understand (or try to understand) her.

What I really enjoy in Lively’s novels is the idea that we are, somehow, composites of selves, that ‘if a place is haunted, it is perhaps with the ghost of ourselves, both past and future.’ Her ‘anti-memoir’, Making It Up, explores this brilliantly: the splintering chains of consequences that make up a life and how different the ‘story’ could have been. It reads like a series of short stories in which Lively riffs on aspects of her own life and imagines how things could have turned out differently.

Then there’s the way she writes. Lively can tell, tell, tell and not show, for pages on end, with little dialogue. It’s how she tells, what she notices, the precise details she chooses to home in on – and always with her trademark taut style. She takes an almost phenomenological view of cities and landscapes – never more so than in City of the Mind, which was proving almost too densely psychological and disorientating for me at first, but which turned out to be a satisfyingly slow burn.

Top recommendations? Heat Wave – pathetic fallacy par excellence, where Lively ratchets up the tension between a mother, daughter and the daughter’s husband during a long, hot summer (remember those? Oh wait, we just had one!). How It All Began for some of her best writing on age, being young, identity, reading, the importance of stories, love, marriage and human interaction. Making It Up – for narrative innovation. And Consequences – an immensely moving, but never saccharine, saga spanning three generations of women from the eve of World War Two to the present day.

She’s got a new book out at the moment, Ammonites and Leaping Fish – read more here: http://www.penelopelively.net

And here’s her recent poignant, meditative piece for The Guardian: http://www.theguardian.com/books/2013/oct/05/penelope-lively-old-age

Do read thee some Lively – you won’t regret it.